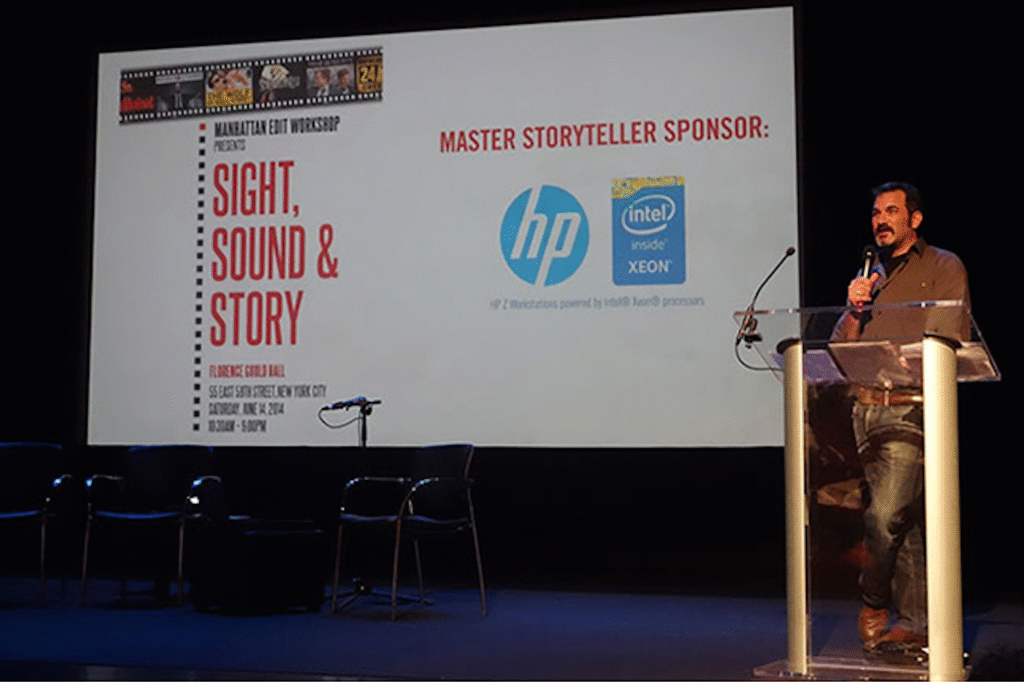

Now an annual event, Manhattan Edit Workshop’s Sight, Sound & Story, held earlier this summer, offers a chance to hear top editors via a non-stop day of panels and tech demos. If you’re in the New York area, you already know that MEWShop is a leading trainer for hands-on know-how of all the major editing apps, as well as the programs you turn to for color correction and compositing, too. With Sight, Sound & Story, MEWshop’s founder and owner, Josh Apter, has created something that goes well beyond the classroom, giving a sense of aspiration to editing students and still learning professionals alike.

As in previous years, everyone gathered in the comfortable confines of the Alliance Française’s Florence Gould Auditorium on East 59th Street. We all sat down with anticipation, ready for the nearly 12 hours of talk, screenings, food, tech demos, and free software giveaways that would come before the last words would be said in a remarkable remembrance by Steven Spielberg’s longtime editor, Michael Kahn, ACE.

Anatomy of a Scene: Documentary Editors Deconstruct Their Work Penelope Falk, Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work, The New Public David Teague, Freeheld, E-Team, Cutie and the Boxer, Mondays at Racine Jonathan Oppenheim, Paris is Burning, The Oath, Streetwise

Garrett Savage, Ready, Set, Bag!, My Perestroika, & Board President of “The Karen Schmeer Film Editing Fellowship”, moderator

Discussion began after the screening of sections of The Oath (2010), a documentary directed by Laura Poitras and edited by Jonathan Oppenheim. The film revolves around two men, one who became Osama bin Laden’s bodyguard (Salim Ahmed Hamdan), and another who became his driver (Abu Jandal). Access to the bodyguard wasn’t going to happen; he was in the US prison compound at Guantanamo, with no outside contact beyond his lawyer.

Poitras spent time shooting in Yemen, and that early sequence is the one we would see and hear discussed. In dramatic you-are-there documentary-style segments, Poitras and crew first met Abu Jandal in a tribal area that turned out to be one actively targeted for bombardment by the US-backed Yemeni government. In the interview we first saw, the documentary’s world turned into a tense scramble as bombs detonated nearby, close enough so that the crew were showered with parts of the traditional inbal home’s walls. Poitras didn’t want a standard documentary’s voiceover telling you what you are seeing. Instead, the idea was to highlight Abu Jandal’s contradictory nature. This would be tricky because he was, as they say in Yiddish, a real schmoozer. He won people over with his easy talk.

Whether he was with his son and a cadre of Muslim pupils, or being interviewed by Western media, Abu Jandal knew how to sound convincing. Oppenheim had a clear approach in dealing with this slippery media master. “We decided to take out the cutaways,” he says. “I did away with those as they made the figures romantic. Instead, I wanted to undermine the character by letting him speak directly and at length.

For Oppenheim, editing starts to come together after he creates a nodal’ scene. Nodal scenes are scenes that collect or organize the behavior of a character. “These are the things you show in a documentary. These are the scenes that have to come together earlier on so that later scenes come alive.” But that was disorienting,” says Oppenheim. While we did a lot of intercutting in the earlier version, in the final version, we stayed with the

Key scenes without usina distractina cutawavs. Oppenheim said it was important to keep the person’s voice, even if you have to make the viewer read subtitles. Story is a web of content, he noted, and how a person spoke was a key part of that. Penelope Falk concurred. A documentary editor who works with projects in many languages, “I won’t cut unless I have subtitles,” says Falk. She talks about beginning her editing sessions by screening dailies chronologically. “I can’t cut before that,” she says. “I’m tracking my emotions throughout. I’m tracking the storyline, the character, and potential story arcs. Finally, I’m considering the film behind the film.

Stories and photos by Dan Ochiva